The Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), extends controls, analysis, decision points, preventive controls and record keeping to each link in the food chain. It also shifts more control on preventive measures. While HACCP focuses on biological, chemical, and physical hazards Hazard Analysis Risk-based preventive controls, HARPC extends these to include Radiation, natural toxins, pesticides, drug residues, decomposition, parasites, allergens, unapproved food or color additives, naturally occurring hazards and intentionally and unintentionally introduced hazards round out the list of HARPC related hazards.

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) and Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls (HARPC) share more than just four letters. They’re both food safety standards based on prevention, but they do differ on execution. Their differences and similarities aren’t as important as the way they fit together for most food processors though. A HARPC plan shouldn’t be considered as a replacement but as a necessary upgrade to the conventional HACCP plan. Understanding how the systems fit together is the first step toward implementing both.

HARPC as an Upgrade to HACCP HACCP is already widely used due to requirements from retailers, auditing standards and inspectors, although the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

only mandate it for meat, seafood and juice products. HACCP has been continually developed and updated. It requires a multi-disciplinary team for implementation and follows prescriptive steps. HARPC covers food safety concerns beyond CCPs and is mandated by FDA for most facilities, with some exemptions. Instead of only looking at process steps where controls can be applied, HARPC relies on the applicable FDA regulations, standards and guidance documents to develop a preventive control plan.

How HACCP Works

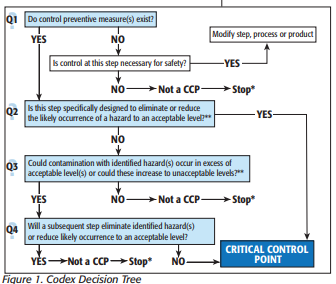

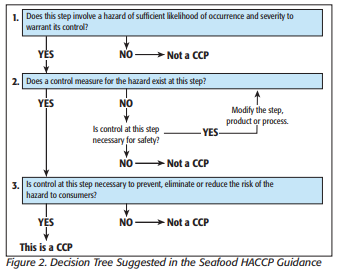

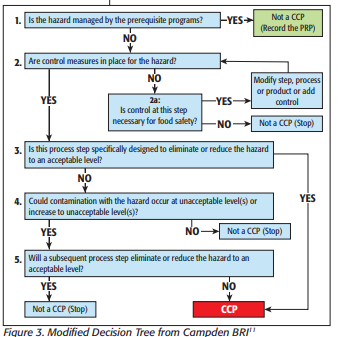

HACCP is a globally recognized, risk-based preventative approach recommended by the Codex Alimentarius Commission (Food Code) and the National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods. The primary goals are to prevent occurrences of the hazard, or eliminate or reduce the food safety hazard to acceptable or safe levels.

HACCP plans are developed, implemented and maintained by a multi-disciplinary team.

Even though HACCP programs for food establishments may be voluntary (unless specified by regulations, industrial standards or customers), it does not absolve a facility from implementing Current Good Manufacturing Practices and other relevant prerequisite program requirements necessary to maintain the safety and legality of the food products. Auditors, inspectors, customers and other stakeholders may inspect the HACCP or food safety plan.

How HARPC Works

In brief, this preventive control system mandated by FDA’s Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) is to be implemented by all food establishments unless specifically exempted. Thus, it applies to food facilities in the U.S. that manufacture, process, pack, distribute, receive, hold or import food, and to those firms exporting foodstuffs to the U.S. Preventive controls are science-based and adequate to significantly minimize or prevent identified hazards “known or reasonably likely to occur” for each type of food subject to the relevant FDA regulation. The HARPC plan is developed, implemented and maintained by a team of “preventive controls-qualified individuals” as defined in FSMA, who have been trained or are sufficiently conversant with the FSMA Preventive Controls for Human Food rule and any other relevant FSMA regulations.

Recap of Key Differences between the Hazard Analysis Methods

The three conventional types of hazards that are addressed in HACCP plans— physical, chemical and biological—are

accompanied by many more concerns in HARPC plans.

Radiation, natural toxins, pesticides, drug residues, decomposition, parasites, allergens, unapproved food or color additives, naturally occurring hazards and intentionally and unintentionally introduced hazards round out the list of HARPC related hazards.

CCPs versus Preventive Controls

CCPs during process steps are central to HACCP. Each control point must include measurable critical limits—the temperature and length of time a sauce must be held at, for example, to be considered a kill step. The objective of each control step is to prevent, eliminate, or reduce food safety hazards to a safe and acceptable level.

Food safety measures that aren’t specific to the process, such as personnel hygiene, are covered under Standard Operating Procedures. HARPC focuses on preventive controls that are science- or risk-based, and should be adequate to “significantly minimize or prevent” known or foreseeable hazards for each type of food subject to the federal regulations.

You Say HACCP, I Say HARPC: Prepping for FSMA

With the advent of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has some 50 new required deliverables in the form of rules and regulations, reports and guidance to industry with which it must comply. These requirements touch every area of our food supply, from growers to harvesters, packagers and distributors, importers and warehouse holding facilities and the list goes on.

What was a function of compliance through the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) plan of keeping safety in check on seafood and juice products has morphed into much more robust Hazard Analysis Risk-based Preventative Controls (HARPC) for FDA-regulated food products. Prevention is the key to safety.

Food companies are preparing for FSMA in a multitude of ways, long before the finalization of all rules. Some areas of preparation are more straightforward, such as reviewing and revising record keeping and documentation procedures, whereas others are less clear, such as determining the best method for insuring the FSMA compliance of suppliers. Whichever issue companies see as their most pressing, one of the biggest questions facing many is “which rules actually apply to me?”

What Is My Main Business?

FSMA is huge and its rules will reach across the food spectrum. Narrowing down the focus to those areas that apply to your business will help to break FSMA down into smaller bites that are easier to digest.

“FSMA has a lot of “if – then” decision points, sometimes nested within decision points,” says Charles Breen, senior consultant for EAS Consulting Group, LLC. “IF the firm makes an acidified food, THEN the requirement for human food microbiological preventive controls do not apply, BUT other parts do.” There is a lot to consider.

Sit down with your team and make sure you fully understand how your business operates from top to bottom. From where do you get your materials? Where does your supplier get their materials? How does your facility run? Understanding the intricacies of every aspect will enable you to get a handle on your focus.

Based on the current proposed rules, “Go through a decision tree process and decide what applies and what does not,” says Breen. “Then look within current staff and see who knows the most about the three hazard areas, microbiological, chemical and physical, and their applicability to the processes used at an individual food facility.” Regarding the question of the requirement for qualified individuals (QI), Breen suggests “a qualified individual for chemical and physical hazard analysis [is likely to] be in-house more often than QI for microbiological hazards. Until FDA clarifies the standardized curriculum for a QI, firms should move forward using whoever is on hand now with the best facility specific information, and look outside as needed.”

What are the possible cracks that things can fall through?

Like it or not every business has an area that can more easily fall through the cracks than others. Those in the business of food, however, must be extra vigilant to prevent those small slips and oversights from happening. Period.

Review your procedures and food safety plan from top to bottom, from how you bring in and verify your suppliers and supplies to the conditions in which items are stored, maintenance checks and operations of your equipment, sanitation concerns, employee protocols, recall plans, allergen controls, everything. Now determine what is missing. Have you addressed all microbial, chemical, radiological and physical risks? The missing link could be as simple as the requirement for employees to wash hands. It could be more intricate such as verifying the (proposed) microbial standards of water applied in the growing of produce.

FSMA requires moving from merely documentation of safe operation to documenting the mechanisms for prevention in the support of safe operation. That’s where HARPC comes in. Identifying those areas of concern which are known or reasonably foreseeable and subsequently addressing those issues in writing, will help your company to be compliant with all things FSMA. This will prove essential in the event of an FDA question with regards to your product.

Review Your Labels

“The Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) as amended by the FSMA now identifies food allergens as a food safety hazard that must be evaluated and controlled in section 418(b) of the FD&C Act. In particular, section 418(c)(3) requires preventive controls to assure that food is not adulterated under section 402 or misbranded under section 403(w),” says L. Robert Lake, senior consultant for EAS Consulting Group. “The Preventive Controls provisions of the FDA Part 117 proposal require a hazard analysis of known or reasonably foreseeable hazards to human food, including food allergens.” So while you are going through your hazard risk assessment, make sure to take into consideration “food allergen cross contact,” or the contamination by a food allergen of a food not intended to contain that food allergen.

HARPC

With the HARPC rules for human and animal feed scheduled to be published in August 2015, now is the time to think prevention. FDA offers Web-based tools such as a food defense planner, and there are multitudes of excellent articles and blogs in Food Safety Magazine that can get you thinking in the right direction. Bringing in an expert on FSMA for a readiness analysis and assessment of where your company is both strong and lacking in FSMA is another option. An independent advisor is often able to more clearly see potential lapses that can be overlooked by those in the trenches.

“Almost no food business in the U.S. is starting from zero when thinking about FSMA compliance,” says Breen. “I am confident that FDA will provide a lot of guidance, advice and assistance to help food firms understand their new responsibilities and obligations.” However, you need to be prepared. Start now if you haven’t already. These rules will be the largest change to FDA policy in many decades. Everyones compliance and participation with FSMA is not only required by law, but is a path forward to a safer process of food safety.

Don’t wait to start preparing for FSMA. The time for action is NOW!

The ABCs Of Building A Food Safety Plan: From HACCP To HARPC

The FDA required hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP) for juice and seafood, and the USDA for meat and poultry. The Food Safety Modernization Act’s (FSMA) proposed Preventive Controls rule for Human Food requires a written Food Safety Plan (FSP) be developed using the hazard analysis risk-based preventive control (HARPC) approach. A preventive approach to food safety is nothing new. But the HARPC approach is a new shift in thinking.

We first define, what HARPC approach is, explain how HARPC is different than HACCP, and how employing this thinking helps you arrive at developing a Food Safety Plan.

HACCP is an international standard that has seven principles used to develop a plan for each product or product type in operation. The FSP using the HARPC approach is a new preventive framework designed to identify specific hazards in addition to traditional HACCP critical control points (CCPs) for processing and take appropriate steps to counter the hazard before a food-safety event occurs. The details below outline the differences in the approach in the context of building an FSP.

Step 1 — Qualified Individual

Developing an FSP with the HARPC approach is a holistic method for a food safety system. The first step is to identify the Qualified Individual(s) (QI). This person is required to have education and experience relevant to food safety and the QI is required to develop the FSP. HACCP requires at least one person to be HACCP Certified, but the development of the HACCP plan is performed by the HACCP team.

Step 2 — Identify The Food

The second step in an FSP is to identify the food, including a product description, intended consumer, reasonable and foreseeable uses, ingredients, processing methods, labeling, packaging, storage and distribution, shelf-life, etc… Similarly, HACCP requires a preliminary task of describing the product. The intent of this is to help gain insight into the risks to the consumer.

For example, let’s use a chicken salad sandwich:

– ingredients are all ready to eat (RTE)

– the process is assembly

– refrigeration is required

– this is sold to the general public and food service venues such as cafeteria including hospitals

– storage and distribution is temperature controlled

– shelf-life is one week

Step 3 — Follow A Flow Diagram

There is no requirement in an FSP for a flow diagram; however, there is for HACCP. I believe, like the FDA has stated in the proposed preventive controls rule (PRC) preamble, a flow diagram is a helpful tool. It is the identification of the product “life-cycle” as soon as it starts in the facility, until it leaves your control. What better way to identify all “known or reasonably-foreseeable” hazards associated with a product than to follow a flow diagram, which leads to step 4.

Step 4 — Identify The Hazard

When considering all known or reasonably foreseeable hazards in the FSP, there are three types of hazards to address: biological, chemical (including radiological), and physical — includes economically motivated adulteration (EMA). There is an expectation that the final rule will require control of EMA, but precisely how that will have to be undertaken is unclear at this point. HACCP addresses the three hazards as well, but does not specifically call out radiological and does not include EMA. For both the FSP and HACCP, the list of hazards must be documented.

Step 5 — Evaluate Hazards

Once known or reasonably-foreseeable hazards are identified, the facility needs to determine if any hazards are “significant.” In the re-proposal of the PCR, “significant” hazard replaced hazards that are “reasonably likely to occur,” which is HACCP terminology. One reason for the terminology change is to get the industry thinking “beyond HACCP” since there are ways to control significant risks that do not fit nicely into the seven steps of HACCP. Some questions to consider in making this determination are:

– Does the facility already have measures in place to control the hazard?

– Has the facility recalled this product due to this hazard?

– Are there customer complaints related to this hazard?

– Has this hazard been the cause of an outbreak or a caused a recall of product at another facility?

– If this hazard were discovered in product, would it trigger a Class I or Class II recall?

– Is there scientific data that suggests this hazard is commonly associated with the product?

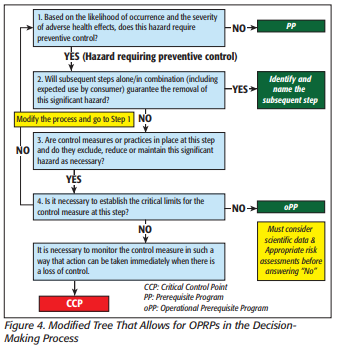

If a hazard is determined significant, it will require a preventive control. You need evidence to support conclusions about hazards, especially if a conclusion is that a hazard is not significant. In regard to HACCP, there are steps to determine if the reasonably-likely-to-occur hazard requires a CCP, but it does not recognize other controls as preventive controls.

Applying this thinking, let’s go back to the example of the chicken salad sandwich and discuss a few potential significant hazards.

Biological:

– Salmonella from the incoming cooked chicken

– Listeria monocytogenes from the processing facility

Chemical:

– Allergen from the mayonnaise and bread (Milk, Eggs, Wheat)

Physical

– Metal hazard from equipment (blender) and utensils (knives)

Each significant hazard must have at least one PC in place. A PC is a reasonably-appropriate procedure, practice, and process to significantly minimize, eliminate, or prevent a significant hazard. Examples of PC are process, sanitation, allergen, employee hygiene, supplier control, and recall plans. HACCP identifies a CCP as a step at which a control is applied to prevent or eliminate a food safety hazard to an acceptable level.

HACCP uses CCPs, critical control points, and HARPC uses PCs, preventative controls.

For example, applying HACCP to the risk of Listeria monocytogenes from the environment, the resulting control is a pre-requisite program (PRP). This PRP would be deployed without any specific program requirements. Applying HARPC principles, the control is a sanitation PC which requires monitoring, verification, corrective action, records review, and reanalysis. See how this approach is moving beyond HACCP?

Step 7 — Validate Preventive Controls And Establish Parameters

Both the FSP and HACCP have similar definitions for validation; the scientific and technical basis to show that a control (CCP or PC) significantly minimizes, eliminates, or prevents the hazard being controlled. HACCP has critical control limits and HARPC has parameters, they are both the specific values that must be reached/maintained (ex: pH, time, temperature, volume or flow rate, contact time, etc…).

Step 8 — Monitoring CCPs

For the FSP and HACCP, monitoring is a documented and planned event (measurement or observation) at a set frequency to ensure a CCP or CP parameter is achieved. Monitoring serves three purposes: it’s an early warning of a potential problem, it shows effective implementation of the control, and it generates records for verification.

Step 9 — Implement Corrective Actions

If the PC is not implemented according to its pre-set parameters, and similarly, a CCP per it critical limits, the product affected by that loss of control is presumptively adulterated/misbranded. Therefore, action must be taken in both instances. Corrective actions must be pre-established and documented for the PC and CCP.

The FSP identifies normal corrective actions to a PC. These are problems which occur without a pre-established corrective action. In all instances, a corrective action still needs to be performed, such as immediately placing on hold all implicated product. Normal corrective actions drive a reanalysis of the FSP to include the new significant hazard.

The FSP and HACCP consider verification activities, not including monitoring, that show the HACCP plan or CP is working as implemented.

The FSP requires the owner, operator, or agent-in-charge to verify that monitoring is being conducted and appropriate decisions about corrective actions are being made. Realistically, these activities will be delegated to the Quality and Food Safety personnel.

Recall Plan — The FSP also requires the development of a recall plan, whereas HACCP does not. While a recall plan may be seen by some a reactive tool to respond to a crisis, the FDA sees it as a proactive, preventive tool to be prepared to respond in the event a crisis should occur.

So what does this all mean to you? If you are following a HACCP plan, you have a good start for building a solid, facility-specific FSP. Be sure to enlist a project team, make a plan that is achievable, including specific milestones, such as updating programs for compliance with the new GMPs, identify all products or categories of products, perform a HARPC-based hazard analysis, and identify preventive controls.

FSMA – FDA Food Safety Moderinazation Act

= $u_time + 86400) {

echo “Page last modified on “;

the_modified_time(‘F jS, Y’);

echo ” at “;

the_modified_time();

echo “, “; } ?>